- Home

- Sofka Zinovieff

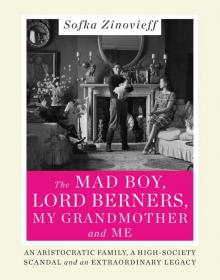

The Mad Boy, Lord Berners, My Grandmother, and Me

The Mad Boy, Lord Berners, My Grandmother, and Me Read online

THE MAD BOY, LORD BERNERS, MY GRANDMOTHER AND ME

DEDICATION

to Vassilis

CONTENTS

DEDICATION

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

1

Fish-shaped Handbag

2

Behind the Rocking Horse

3

Russians, Radicals and Roman Catholics

4

A Delightful Youth

5

Et in Arcadia Ego

6

Boys and Girls

7

Fiends

8

Follies and Fur-lined Wombs

9

The Orphan on the Top Floor

10

In the City of the Dreaming Dons

11

Gosh I think She’s Swell

12

The Pram in the Hall

13

Put in a Van

14

‘From Catamite to Catamite’

15

The Nazi

16

Robert’s Folly

17

Purple Dye

18

Blood Ties

19

Dust and Ashes

20

The Bell and the Blue Plaque

NOTES

SELECT BIBLIOGRAPHY

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

INDEX

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

ALSO BY SOFKA ZINOVIEFF

CREDITS

COPYRIGHT

ABOUT THE PUBLISHER

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

The pagination of this electronic edition does not match the edition from which it was made. To locate a specific passage, please use the search feature on your ebook reader.

Pink dove.

i

Moti, Penelope Betjeman’s horse.

v

The drawing room at Faringdon. (© Joanna Vestey)

xii

Jennifer painted by Gerald.

3

Cecil Beaton’s portrait of Gerald, Robert, Victoria and Jennifer. (Courtesy of Cecil Beaton Studio Archive at Sotheby’s)

6

Gerald aged five, 1889.

21

Gerald aged twenty-two, 1905.

29

A creeper-clad Faringdon House.

30

Gerald’s house at Via Foro Romana in Rome.

33

William Crack driving the Rolls-Royce.

42

Julia, Gerald’s mother sits on the steps at Faringdon House with her second husband.

48

Algy, Cyril, Robert and Alan Heber-Percy.

54

Robert’s brothers, Cyril and Alan, changing the guard at Buckingham Palace, 1927.

62

Kathleen Meyrick with Robert at the races.

70

The Mad Boy.

72

Gerald in playful holiday mood.

75

Gerald playing the piano at Faringdon.

82

Coloured doves. (© author)

86

Gerald painting Moti, held by Penelope Betjman.

94

Penelope Betjman feeding tea to Moti, watched by Robert, Gerald and a friend.

95

Faringdon House painted by Gerald.

97

Coote, Robert, Penelope Betjeman and Gerald, ready to ride.

100

Maimie and Robert in Italy.

104

Maimie with her Pekingese Grainger and Robert at Faringdon.

105

A photograph of Robert in Cecil Beaton’s personal album: Horrid Mad Boy. (Reproduced by permission of Fred Koch)

107

Gerald; Doris, Lady Castleross; Daphne, Vicountess Weymouth; Robert

110

A page of the Faringdon House visitors’ book from December 1934 to January 1935

114

Diana Guinness in Italy.

119

A postcard doctored by Gerald.

134

Gerald’s painting of the Folly for the Shell Guide poster.

135

Salvador Dalí’s drawing dedicated to Robert, 1938.

137

’Red Roses and Red Noses.’

142

Elsa Schiaparelli on top of the Folly with Gerald.

143

On the terrace steps at Faringdon: Elsa Schiaparelli, Gerald, Baroness Budberg, H. G. Wells, Robert, Tom Driberg.

145

Gerald and Robert with guests including Alice B. Toklas, Gertrude Stein and Sir and Lady Abdy.

154

Igor Stravinsky and Gerald at Faringdon.

155

Althea Fry gazing at a bust of Dante.

160

Oare House today. (© author)

163

Pixie, Jennifer’s governess, reading to her charge at Oare.

166

‘She-Evelyn’ Waugh, Jennifer’s aunt.

169

Geoffrey Fry: bookish, bisexual and coldly critical of his wife and daughter.

172

Jennifer aged about sixteen.

173

Jennifer, 1930s party girl.

177

Prim and Jennifer on a ship headed for holidays.

178

Jennifer’s record of her stay at Faringdon in 1938.

184

A page from Jennifer’s album, showing Robert and her in sultry mood

185

Frederick Ashton, Robert, Maimie, Constant Lambert, Gerald, Vsevolode, ‘Prince of Russia’, at Faringdon, Easter 1939.

187

Robert by an oasis in Arabia. (© Gerald de Gaury)

197

Clarissa Churchill, posing as a statue.

208

Winnie, Princesse de Polignac, reading the paper. (Courtesy of Cecil Beaton Studio Archive at Sotheby’s)

223

Bride and groom looking tense at the reception at Claridge’s.

236

Jennifer, Gerald and Robert in Gerald’s wartime study-bedroom. (Courtesy of Cecil Beaton Studio Archive at Sotheby’s)

242

The new family with their nanny. (Courtesy of Cecil Beaton Studio Archive at Sotheby’s)

250

Gerald with Victoria. (Courtesy of Cecil Beaton Studio Archive at Sotheby’s)

251

Cecil Beaton’s photographs of Lord Berners and the Heber-Percys published in the Sketch. (Courtesy of Cecil Beaton Studio Archive at Sotheby’s)

252

Victoria’s christening at All Saints’, Faringdon.

253

Victoria with Jennifer at Oare.

263

David and Prim Niven with their new baby.

273

Victoria sitting on Gerald’s lap.

279

Jennifer and Alan Ross on their wedding day, 1949.

281

Alan rowing.

281

Gerald on the day-bed in his study.

285

Telegram from Marchesa Casati.

289

Roy Hobdell’s mural in the bathroom. (© Oberto Gili)

291

One of Roy Hobdell’s trompe l’œil works commissioned by Robert. (© author)

292

Victoria with her half-brother Jonathan.

301

Victoria in Harpers & Queen, aged sixteen. (Courtesy of Cecil Beaton Studio Archive at Sotheby’s)

303

Victoria and Peter’s wedding reception, 1960.

&

nbsp; 305

Jennifer, Victoria holding the author, and Alathea at Oare, 1962.

307

The author, aged about twelve, in Putney.

309

Robert with Manley, the Great Dane.

316

The old Mad Boy, horned and ready for a party.

324

Robert with the author, mid-1980s. (© Jeremy Newick)

334

Robert’s coffin is carried from the house towards the church.

348

Rosa preparing dinner.

350

The Faringdon photo album showing Robert, Mamie and others on the beach at Ostia.

355

Leo’s wedding to Annabelle Eccles. (© Mario Testino)

361

The author and Mario Testino at Faringdon, Easter 1988.

369

Victoria’s whippet, Nifty, dyed mauve.

370

Imitating the Cecil Beaton photograph of 1943. (© Jonathan Ross)

375

Vassilis with Anna and Lara, spring 1996. (© author)

386

On the back lawn during a visit to Faringdon, Easter 2009. (© author)

387

Andy Smith digging for Gerald’s ashes, helped by Jack Fox. (© author)

389

The author unveiling the blue plaque for Lord Berners on his Folly, 2013. (© Stephanie Jenkins, Oxfordshire Blue Plaques Board)

395

THE DRAWING ROOM AT FARINGDON: PORTRAIT OF THE YOUNG ROBERT HEBER-PERCY BY GERALD BERNERS; PORTRAIT OF BERNERS HOLDING A LOBSTER BY GREGORIO PRIETO; JENNIFER’S FISH-SHAPED HANDBAG ON THE CHAIR, AND ONE OF THE PINK DOVES ON THE TABLE

CHAPTER ONE

A Fish-shaped Handbag

HEN I WAS SEVENTEEN, my mother took me to stay with her father for the first time. I knew that she didn’t really like him, that he was homosexual, and that his house was remarkable. It took less than two hours to drive to Oxfordshire from London and I was full of anticipation as we arrived in the market town of Faringdon. Heading towards the church, we passed through an old stone gateway and into a driveway that began almost sinister, darkly hedged-in like a tunnel. Then an unexpectedly dramatic vista opened up between the trees; the town was left behind and an immense stretch of green countryside was revealed. Swinging to the right, we arrived in front of the house almost before we had seen it. A four-square, grey building, it was grand but not intimidating, handsome yet playfully gracious and as enticing as a Georgian doll’s house.

As we came to a halt, the gravel crunched luxuriously and I watched in wonder as a flock of doves, coloured jubilant rainbow shades of blue, green, orange, pink and mauve, fluttered up like a hallucination. They swooped a couple of showy circuits around the roof of the house before landing nearby and picking matter-of-factly at dead insects on the wheels of our car. My mother explained that these dyed birds were a tradition, started by Gerald Berners many decades before. I had gleaned a little about Lord Berners – in particular that Robert, my grandfather, had been his boyfriend. I also knew that Berners had been an eccentric who composed music, wrote books and painted, and that he had left Faringdon House to Robert when he died. The 1930s had been their glory days together, when Gerald Berners created an aesthete’s paradise at Faringdon. Exquisite food was served to many of the great minds, beauties and wits of the day. The place was awash with Mitfords, Sitwells and other visitors as diverse as Igor Stravinsky, Gertrude Stein, Salvador Dalí, H. G. Wells, Frederick Ashton and Evelyn Waugh. But my mother was not enthusiastic about the glamour or impressed by the famous old friends. She associated the place with snobbery, camp bad behaviour and a lack of love and affection. She had tried to get as far away as she could from this environment, and hadn’t wanted to bring her three children into contact with it.

Robert was standing on the pillared porch under the crystal chandelier, a bullish boxer dog by his side. In his late sixties, my grandfather was wearing a well-cut dark blue suit and holding a drink and a lit cigarette in one hand. A wave of thick, metallic-grey hair swept off his forehead and unkempt eyebrows pitched at a rakish angle. I kissed him – he was my relation, even if I didn’t know him. Nobody had told me then that his long-standing nickname was the Mad Boy, but his expression was obviously mischievous, his laugh a raucous bark. He must have been amused when Victoria, my thirty-five-year-old mother, and I introduced our boyfriends – hers much younger, mine much older; it was 1979. Robert turned our unlikely group into a joke for the next weekend’s guests.

We were led through the hall filled with pictures and plants, and under a strange staircase that started double and then flew daringly overhead as a bridge to the first-floor landing. The drawing room ran the entire back length of the house, with one end pale, the other dark green. It was filled with light, as though we were very high up, and five tall windows gave on to an astounding view across the Thames Valley to the blurred horizon of the Cotswolds. To one side, a wooded valley led to a stone bridge and a lake, and to the other, cattle grazed in rough grass beyond the ha-ha.

Robert distributed champagne in pewter tankards and we took in the long room, filled with things that had mostly been there since Lord Berners’s day: ornate gilt mirrors, Aubusson rugs, a painted day-bed, a grand piano, antique globes, glass domes with stuffed birds and a collection of old wind-up mechanical toys. There were tall arrangements of flowers from the garden and the walls were covered with paintings – several by Corot, and some landscapes in a similarly muted style, which Robert said were by Gerald.

Lying on the seat of a gilded rococo chair was a white wicker handbag shaped like a fish and with a bamboo handle. ‘That belonged to Jennifer – your grandmother,’ Robert said to me, grinning. ‘She forgot it when she left, and it’s been there ever since.’ Like so much in the house, it was hard to know whether this was a joke. A wooden sign on the front door said ‘ALL HATS MUST BE REMOVED’; others in the gardens warned ‘BEWARE OF THE AGAPANTHUS’ and ‘ANYONE THROWING STONES AT THIS NOTICE WILL BE PROSECUTED’. Robert also pointed out an unframed canvas propped on the top of the dado rail – an oil portrait of Jennifer by Gerald. She is gorgeous, with full red lips and brown hair swept away from rosy cheeks. Her eyes are dark and slightly protuberant, gazing inquisitively off to the side. Gerald made her pretty enough for a chocolate box, but you can tell that she is not necessarily happy. Maybe she really had left in such a hurry that she forgot her bag.

JENNIFER PAINTED BY GERALD

A Victorian music box in the hall tinkled a song to summon us for lunch and we were placed, slightly formally, at the round table in the dining room. I was introduced to Rosa, the Austrian housekeeper who had lived there for many years and was rumoured to celebrate Hitler’s birthday. With dark grey hair pulled into a tight bun, and high-boned, florid cheeks, she seemed a bit flustered, though I quickly saw that the house was her realm almost as much as Robert’s. Unmarried and utterly dedicated to her work, Rosa was last to bed, shutting up the wooden shutters in the drawing room after guests had retired, and first up, picking mushrooms at dawn, laying fires (lit at the slightest hint of summer chill) and preparing substantial breakfasts. Her hands were swollen and red, but they were capable of fine work and had produced an astonishingly elegant meal for us.

My memory of that first warm July day is of cold poached fillets of sole in a horseradish-and-cream sauce and tiny vegetables from the garden that could have fitted on dolls’ plates – buttery new potatoes the size of quails’ eggs and green-topped carrots no larger than babies’ fingers. Afterwards, there was a dark crimson summer pudding, its fruity entrails swirling into the cream on our plates. Robert was master of ceremonies, pressing an electric bell under the table to summon the next course, and requesting that the ladies get up in order of seniority and serve themselves from the sideboard, followed, when they had returned, by the men. There was some sweetish white wine and Robert smoked between courses, filling his glass ashtray, carved with racing dogs, one of which

was set at each place. My new-found grandfather was full of risqué humour and provocative remarks, but he evidently liked proper etiquette as a bedrock. I assumed it had always been like that; these manners felt long-established.

In the afternoon we walked in the gardens. The eighteenth-century orangery was filled with mirrors and large oil paintings – ‘Gerald’s ancestors,’ said Robert, explaining that Lord Berners had not wanted too many of his haughty forebears in the house and had banished a number to the stables, from where some had ended up in here. There was mildew creeping up the crinoline of one of these unwanted ladies, but the general effect was so pretty it didn’t seem wrong. The place was inundated with the intoxicating scent of pale Datura flowers – the angel trumpets that have long been used for hallucinogenic love potions and poisonous witches’ brews. Outside, a small lily pond contained the bust of a whiskered Victorian gentleman submerged at the centre, ‘As if he is the captain of a ship that has sunk in the pond, and he is alone on deck, at attention for ever, with the water up to his chin.’1‘General Havelock,’ explained Robert, gesturing to the humiliated military man. A pattern was already emerging: the joy of pricking pomposity, of laying traps to surprise or delight.

The House on Paradise Street

The House on Paradise Street The Mad Boy, Lord Berners, My Grandmother, and Me

The Mad Boy, Lord Berners, My Grandmother, and Me